Farm to science: Rutgers Climate Institute is partnering with Duke Farms to reduce agriculture’s carbon footprint

If everyone does not do what they can to keep global temperatures from rising, large parts of the Earth may soon become uninhabitable, Michael Catania said.

“The consequences are very serious,” he said. “That is why Duke Farms is trying to not only reduce our own carbon footprint, but also demonstrate natural climate change solutions that will take carbon out of the atmosphere and store it in soil and vegetation.”

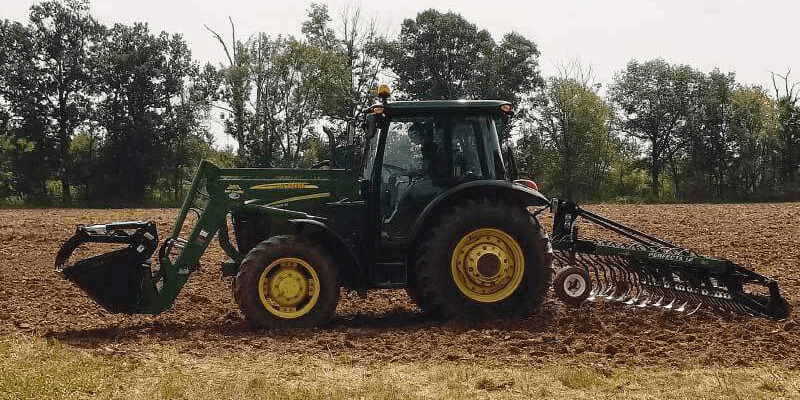

Therefore, in addition to using low-impact, organic, sustainable and wildlife-friendly farming techniques, Duke Farms in Hillsborough is now also demonstrating a wide range of nontraditional farming and planting practices, including low-till, no-till and cover crops, Catania, executive director, said.

“While there has been much discussion of these solutions in recent scientific literature, what is needed now is scientifically valid data generated by monitoring recent restoration projects and changed farming practices,” he said.

That is where the Rutgers Climate Institute at Rutgers University in New Brunswick comes in, Catania added.

“Our partnership with Rutgers should address that need and help demonstrate the efficacy of using natural climate solutions,” he said.

Duke Farms entered into a five-year-plus partnership with the Rutgers Climate Institute in March to begin collecting data that will help document the carbon implications of changing over to more natural methods, Marjorie Kaplan, associate director of the Rutgers Climate Institute and research project director, said.

“The very forward-thinking team of land managers at Duke Farms is providing us with an exciting living laboratory opportunity to conduct research regarding carbon sinks that will have value for these types of vegetative and agronomic systems within and beyond our region,” she said.

With a staff of eight, Rutgers Climate Institute is utilizing Duke Farms’ 2,742 acres of land to conduct on-site research and monitor projects that will reduce and store carbon emissions.

“We are actually conducting field sampling rather than relying on literature values,” Kaplan said.

This year, she said she hopes to collect baseline data that will help her team better understand carbon stocks associated with the various land types and management strategies at Duke Farms.

“We are looking across a range of land cover and land-use types, including wetlands, grasslands, forests and agricultural systems,” Kaplan said. “The measurements will be at greater depths than many other studies, allowing us to better understand the mechanisms of storage.”

The plan is to ultimately devise further strategies on how Duke Farms and others can continue to remove significant amounts of carbon from the atmosphere and store them in “carbon sinks,” or various soils and vegetation, Kaplan added.

Catania said he is thrilled at the idea of Duke Farms becoming carbon neutral or even carbon negative.

“We want to work with Rutgers to develop best practices in maximizing carbon storage and to have real data to show people that if you farm and plant this way, here’s how much carbon you can lock up,” he said.

Catania said he hopes to encourage more farmers to adopt these techniques to help address climate change and lower the adverse impacts it will have on New Jersey and elsewhere.

“The biggest challenge facing New Jersey farmers is climate change,” Catania said. “We are getting clobbered. Last year, we had almost twice the amount of annual precipitation and heavier storm events followed by droughts.

“But, it turns out that some of the things we need to do to address climate change will actually provide farmers’ fields with some protection, making their fields more resilient while lowering operating costs and carbon emissions.”

Duke Farms

Its partnership with the Rutgers Climate Institute may have just begun, but Duke Farms’ history goes back more than 115 years.

Beginning in 1893, James Buchanan Duke transformed more than 2,000 acres of farmland and woodlots into the bucolic landscape known today as Duke Farms, consisting of nine lakes, over 18 miles of trails and more than 45 buildings. His fortune was inherited by his daughter, Doris Duke, upon his death in 1925. An environmentalist, Doris Duke envisioned that Duke Farms should serve to protect wildlife as well as become a leader in environmental stewardship, agriculture, horticulture, education and sustainability research.

Now a private nonprofit supported by the nearly $1.9 billion Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and its related entities, Duke Farms opened to free public visitation in May 2012 to inspire visitors with its commitment to conservation.

“With a staff of nearly 60 and our many volunteers and docents, we hosted nearly 400 programs last year for the public, schools and professional training,” Catania said. “We also have a huge community garden program with 473 plots; we farm to provide food at our own café; we host a farmers market; and we host three major festivals annually.”

New Jersey and climate

When the U.S. left the Paris Accords, New Jersey was one of 24 states that joined the U.S. Climate Alliance, Michael Catania, co-chair of the New Jersey Climate Change Alliance, said.

“They are committed to doing everything they can to keep rising global surface temperatures from exceeding 2 degrees Celsius,” he said.

Therefore, New Jersey has set forth a master plan citing the ambitious goal of reducing carbon emissions by 80 percent by 2050, he added.

“That’s a heavy lift,” Catania said.